The name refers to a designated meeting place, a square where an open market was formerly held near Des Plaines and bordered on Randolph Street. There, on May 4, 1886, an historic armed confrontation took place between a group of Anarchists and labor activists and more than 170 armed police officers, who had been assembled at the Des Plaines Police Station a half block away in anticipation of a riot. View case details.

Although Haymarket was a watershed, it was not an isolated or unprecedented confrontation between labor agitators and law enforcement. Since 1877, shows of strength by labor activists and anarchists took place in Chicago, as well as in other parts of the United States, and in Europe and Russia. The labor activists were advocating for greater power and economic security to be given to working people, and in some instances calling for the violent overthrow of the capitalists and the governing authorities. After the railroad strikes of 1877, there had been nearly a decade of escalating strikes, political demonstrations and armed confrontations between workers and police and private militia, hired by management.

Political agitation by labor activists in the campaign to limit the working day to eight hours a day for workers in factories became intense during periods of severe economic depression, for example, from 1883-1886. In the spring of 1886, prior to May 4, the day of the Haymarket confrontation, mass meetings and rallies of several thousand people had been held, and a barrage of literature in English, German and other languages encouraged violent confrontations and challenges to the police and the government over labor conditions and the eight hour movement.

May 1, 1886 had been declared by the federated unions at their national meeting in Chicago in 1884 to be the date when the eight hour system would go into effect throughout the country, with the support of nationwide strikes, if necessary. When that day passed without incident, everyone waited. In the meantime, groups of industrial managers and employers, citizens, and the mainstream press expressed alarm at the prospect of threatened revolutionary action, and inflamed rhetoric on both sides hardened the antagonistic positions of labor and management.

On May 4, 1886, several of the better known labor leaders and anarchists addressed a crowd of sympathizers from the back of a wagon which had been pulled into an alley near the Haymarket. August Spies spoke in English, followed by Albert Parsons, who also spoke in English for almost an hour denouncing the capitalist system, and quoting statistics, as he had on numerous other occasions. Parsons’ speech was followed by a speech in a similar vein by Samuel Fielden, another well known activist.

A light rain started to fall during Parsons’ speech, and the crowd began to disperse, many, followed by Parsons and his wife, Lucy Parsons, and their two children, went to Zepf’s Hall, a nearby meeting place. As Fielden continued to speak the crowd dwindled to a few hundred. In the meantime, however, a police officer had reported to Inspector Bonfield that the speaker was using inflammatory language and exhorting the crowd to violence.

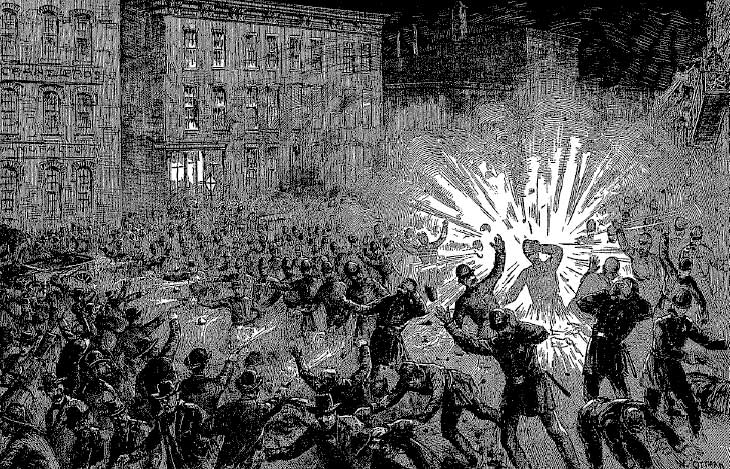

Just as Fielden was concluding his address, Inspector Bonfield and more than 170 armed police marched into the area and ordered those assembled to disperse. Fielden objected and stepped down from the wagon. Suddenly a bomb was thrown at the police, and the police fired. Panic followed. One police officer, Matthias J. Degnan, was killed by the bomb, six additional officers were wounded, some by the bullets of fellow officers. A total of seven police officers, as well as an unknown number of civilians, died in the confrontation.

The public and the mainstream press called for vengeance, the anarchists claimed sabotage, and a wave of popular sentiment against anarchists and labor organizers swept through the city and the country. In Chicago a secret organization of prominent businessmen and employers was formed to counteract the labor activism. Many were arrested, illegal searches were conducted, and rights of free speech and assembly were drastically curtailed. Some labor organizations and activists also protested the violence and supported the government’s response to the bomb throwing. In the meantime, no one knew who threw the bomb or if it had originated in Chicago.

In short order a specially constituted grand jury indicted ten defendants, most of whom were prominent labor organizers and activists, as accessories before the fact to the murder of Officer Matthias Degan by the bomb.

The trial, in July and August of 1886, presided over by Judge Gary, was the cause celebre of the century. Several prominent anarchists and labor activists were among the defendants: Spies, Parsons, Schwab, Neebe, Fielden, Fischer, Engle and Lingg. Parsons had fled Chicago immediately after the incident and remained in hiding in Wisconsin until the first day of trial, when he walked in with his defense attorney and said he was ready to stand trial with his comrades. Several named defendants and coconspirators were never apprehended. All the defendants - except Neebe were found guilty of being accessories to murder and sentenced to death - in spite of the fact that several were not present at the scene when the bomb was thrown. Nor could the State prove who threw the bomb, or if these defendants knew of its existence prior to the meeting. What was amply proved at trial was that these defendants and other anarchists had advocated violence in their literature, books, and newspapers.

In September of 1887 the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the verdicts of guilty of murder by being accessories before the fact, although in the intervening year many questions had been raised about the integrity of the trial and its outcome. The United States Supreme Court refused to intervene and overturn the verdict.

A few days before the scheduled executions, Lingg committed suicide by exploding a smuggled detonator cap in his mouth. In response to public pressure and criticism, the sitting governor commuted the sentences of Fielden and Schwab to life imprisonment, but refused to commute the death sentences of the others. The executions were scheduled to go forward. The public and the government were convinced there would be a last minute attempt to storm the jail and free the prisoners, and the city and the jail were locked down and guarded by hundreds of police in anticipation of another major act of violence by the anarchists. None occured.

On November 11, 1887 the four remaining anarchists whose sentences had not been commuted, Spies, Parsons, Fischer and Engel, were hanged in an unusual, highly ritualized ceremonial execution which was witnessed by selected audience of more than 170 people. When their funeral cortege made its slow procession through the streets of Chicago on its way to Waldheim cemetery, the crowd of silent observers, behind rows of armed policemen, was estimated at more than 200,000.

In June of 1893 Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the two remaining living defendants, Fielden and Schwab, and issued a long statement of reasons for the pardons, criticizing the due process procedures at trial in general and the prejudicial conduct of Judge Gary at trial in particular. The act of pardoning the anarchists, and the criticism of the judge and the manner of trial, were both highly unpopular. The ruling destroyed Governor Altgeld’s prospects for holding elected office in the future. Those who were hanged became martyrs to generations of labor activists. Those who believed the defendants were a threat to public security congratulated one another that public order had been restored with an exemplary punishment.

See also:

- The First Mayday: the Haymarket Speeches (1980)

- Michael J. Schaack, Anarchy and Anarchists. A History of the Red Terror, and the Social Revolution in America and Europe. Communism, Socialism, and Nihilism in Doctrine and Deed. The Chicago Haymarket Conspiracy, and the Detection and Trial of the Conspirators. (Chicago, 1889) (F.J. Schulte and Co.)

- The Library of Congress Collection: Chicago Anarchists on Trial: Evidence from the Haymarket Affair.

- The Chicago Historical Society.