The Race Riot in Chicago in the summer of 1919 left 38 dead, including twenty three black men and boys; and 537 injured, of whom 342 were black, and hundreds homeless. Race riots in other Midwestern and northern cities took place about the same time, as social tensions were aggravated by economic and labor problems after the World War I armistice.

We recommend you download the raw database files for comprehensive searching, but here’s a sample of related cases:

The Coroner’s report on the riot described the events as follows: “Five days of terrible hate and passion let loose, cost the people of Chicago 38 lives (15 white and 23 colored), wounded and maimed several hundred, destroyed property of untold value, filled thousands with fear, blemished the city and left in its wake fear and apprehension for the future…”

Chicago as a national railroad hub, and with its booming industrial economy during the war, had been a magnet for black workers from the South from 1918 onward. The black population in Chicago increased 148 per cent from 1916 to 1919. The Great Migration of blacks from the South to the urban and industrial north and Midwest, encouraged by reports of available jobs in the stockyards and the meat packing industry, by the leading black American newspaper, The Defender, published in Chicago, resulted in dramatic changes in the demographics of many inner city wards, and the creation of new, vibrant black neighborhoods in the city.

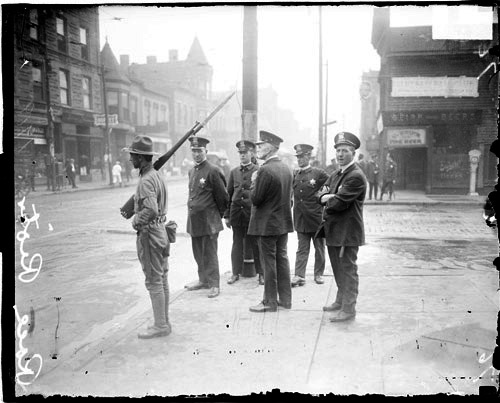

The trigger for the riot was the drowning of Eugene Williams at the 298th street beach on a sweltering July afternoon. Eugene Williams was hit by a stone thrown by a white man on the breakwater. The man had been throwing rocks at the black boys in the water prior to hitting Eugene Williams, but when he was identified the police would not arrest him. Once the riot started, armed gangs roamed the street looking for people to kill. Snipers shot from encampments behind windows; and confrontations between police and citizens were violent. At one point at the corner of Wabash and 35th street, a crowd of 1,500 blacks challenged 100 armed police. At the end of two days of violence, and the burning of neighborhoods, more than 6,000 state militia had been called to the city. On the third day, twelve to fifteen thousand black men and women returned to work at the stockyards under a cover of machine guns. Although more officers, eleven, were killed in 1919 than in any year prior to that time, the only police officer killed in the riot was Patrolman John Simpson, 31, an African American working out of the Wabash Avenue Station.

The armed confrontations may have been over, but aftereffects smoldered longer than the charred remains of the burned buildings. Ironically, the beach where the black boys had gone to swim was not a segregated beach.

For further reading: Cohen, Lizabeth., Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990. This work documents the difficulties and successes of industrial workers (immigrants and racial minorities) to form a union in Chicago before and leading up to the New Deal. It also describes how mass culture permeated the lives of these workers and forged cohesive bonds across race and ethnic lines.

Barrett, James R., Work and Community in the Jungle: Chicago’s Packinghouse Workers,1894-1922. Champaign: U. Illinois Press, 1987. A study of these workers, their political and social identifications, and the long, bitter and brutal battles for unionization.